Cat food

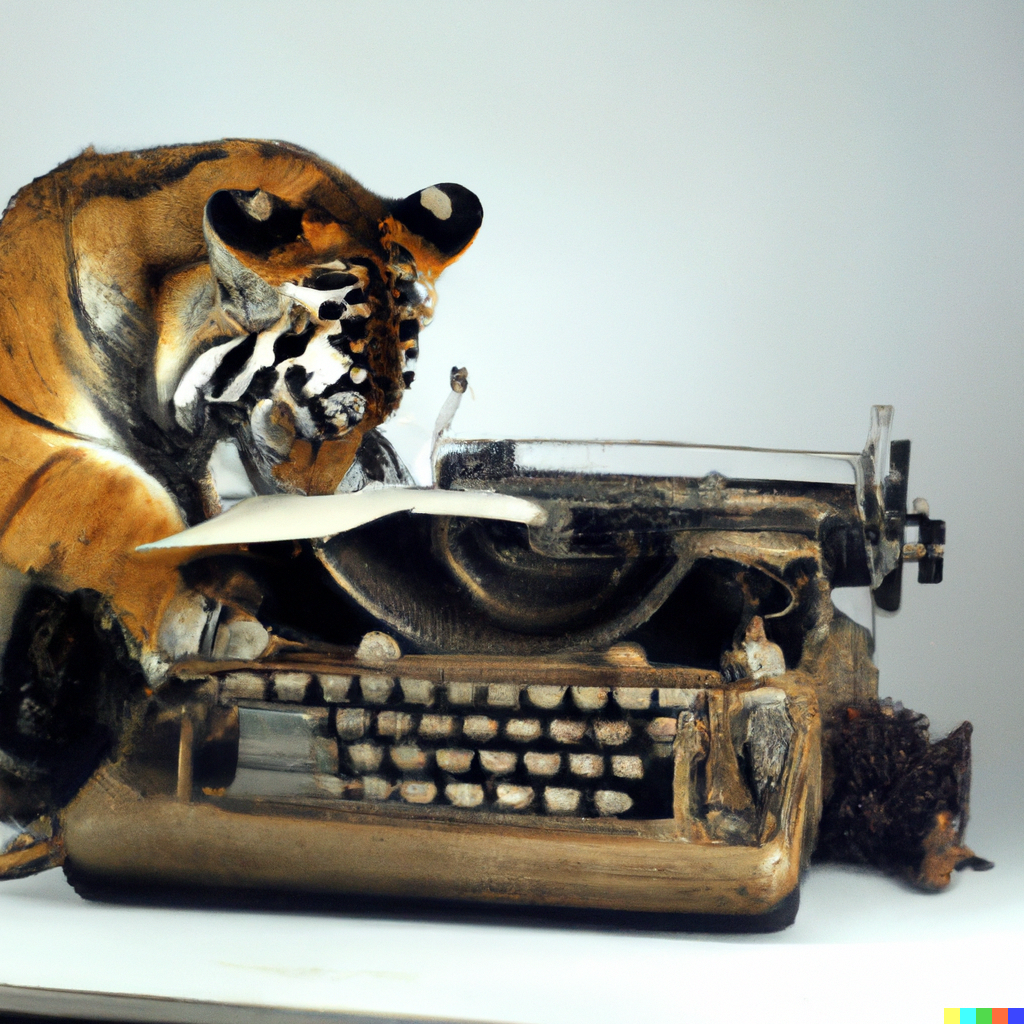

We eat our own dog^h^h^h cat food here at Paper Tiger, so it’s only natural that today’s piece should be composed using the same device we’re reviewing. While long-time readers may recall we tried that strategy with the Instant Pot with disastrous results for the piece and ultimately for Instant Brands, the terms of our settlement with Instant remain confidential.

While not a cooking appliance per se, today’s device does involve high temperature, a certain amount of pressure, and is an appropriate subject for polite dinner conversation. That device is the Pi 40 keyboard kit from 1upkeyboards.com.

What’s a keyboard kit? For some, it’s the ultimate way to precisely tailor the tactility of their computing experience to their very specific mental illness. For others, it can be a great way to learn soldering skills and build an object they will cherish. For me, it’s a rare and fabulous window into computing history.

The Pi 40 kit is mostly a piece of fiberglass. More specifically it’s a laminated sandwich of several such pieces, each decorated with circuit traces and plated holes interconnecting the several plys. It’s a keyboard kit in somewhat the same way that a maple pastry board is an apple pie kit. Just as my pastry board has a recipe for pie crust marked on the surface, the holes and lines on the surface of the Pi 40 prescribe a network of components that, when purchased separately and added, turn the kit into a device. Down goes the Raspberry Pi Pico that will serve as the brain of the thing, down go dozens of diodes that support the keyboard matrix, and down go the many mechanical keyswitches that put the key in keyboard. Fix them all with heat and solder and flux, load some code in the Pi, and you have a keyboard.

You know, flux is really the butter of the home keyboard chef. It’s the first thing in the pan and nobody really wants to talk about how much they use.

The 40 in Pi 40 indicates the number of mechanical keys supported by this board. 40 isn’t enough for the letters to which you are likely accustomed, the digits, punctuation, meta, etc. On the other hand, it’s perhaps two dozen more than you might feel like you need to hand solder to feel a sense of accomplishment. A reasonable balance. The Pi indicates the Raspberry Pi.

The Raspberry Pi Pico is the single-board computer that’s the Raspberry Pi Foundation’s reference platform for their RP2040 microcontroller. It’s a board in the same technical sense that keyboard kit is a board, but the device itself is really more like an old-school DIP 40-pin microcontroller than it is like a small computer. In fact, 40-pin DIP is the original format of Intel 8042 used in the IBM PC as a keyboard controller.

The Pi is a much more formidable computer than that 8042. In fact, it has more than a dozen times more RAM and many dozen times more persistent storage than my first computer, a TI 99/4A, which was also built into a keyboard.

Here, the Pi is asked to do less than play Parsec. It just has to run the open-source QMK firmware that turns the clack clack press-and-release of keys into the USB protocol messages a modern device understands.

QMK may be reason enough to build the kit. Once you buy the microcontroller and a bag of diodes, keyswitches, and keycaps, you’re ready to decide what the keyboard should do. Are you a LISP programmer who wants a key for the letter Lambda? No problem. Would you like a meta key that turns the keyboard into several octaves of MIDI with pitch bend? No problem. Keys that emulate mouse motion and buttons? No problem.

I’m writing this post with a Pi 40 connected to an iPad Pro and I see in it the future of end-user empowerment. It would be easy to invert the relationship between these devices and turn the keyboard into the root of computing and the iPad into a gorgeous terminal — but what kind of computer? An emulated ZX-80? A tiny LISP machine? An HP-48 calculator? An entirely novel system?

Today’s post pairs well with “Food for Thought” / UB40 / 1980.

Member discussion