24k #11 — Télémécanique TSX 17-20

When is scraping the bottom of the barrel a task of joy instead of desperation? When conching chocolate, of course! Also when scouring the internet for the finest in single-origin, late-harvest 24k machines for you.

Conching chocolate and plumbing for content for you share more than that. Both take a long time — so much that joy could fade to bored despair. Automation offers a partial cure. For conching, mechanize away the tedium. For 24k, the little boxes that orchestrate pumps and valves and motors and sensors represent one of the pockets where these machines remain. Peek into the cabinet controlling your favorite chocolate factory or French submarine and you might find a Télémécanique TSX 17-20. It’s the 11th installment installment in the 24 x 24k for 2024 series. I know it sounds like I invented it for the Merrimac Computing Universe but it’s totally real.

These machines, as a class, are called PLCs — Programmable Logic Controllers. If you think that a programmable logic controller sounds a whole lot like a computer, you’re not wrong. You’re not quite right, either. When I was a lad back in the 20th century, we were told that computers were the direct descendant of Jacquard’s loom. The punched cards in this particular narrative tapestry are: that Jacquard builds a loom driven by pasteboard cards, that this loom inspires Babbage to design the Analytic Engine, that this inspires Hollerith to build his card machines, that … and the next thing I remember it was the history of register scoreboarding. Maybe they skipped the part in the middle. Maybe it was covered and I was busy playing Truxton in a sub shop off campus or hacking on something called linux on campus. I need a child’s small fingers to reach into the loom and tie the broken threads of the story back together.

Anyway, somewhere in the middle is the Harvard Mark 1 relay machine designed by Aiken and built by IBM, then the vacuum tube machines ENIAC and Colossus. Poke around and fill in the gaps and you can weave together a seamless story of computers moving from manipulating the coarse cloth of the material world to being textiles themselves with woven core memory and then spinning abstract threads of concurrent execution on pure information. From mechanical pins and levers to electromechanical relays to the electrons themselves and then onto however quantum computers are thought to work. Which, as far as I understand, is much like the last five minutes of the movie Highlander. The quantum computer will understand everything all at once just after it decapitates the last of the classical computers in an epic sword battle. Then the franchise waveform collapses and none of the sequels will attract much commercial attention.

What if the Jacquard looms responsible for all this just kept plugging along and powering business? What if there were other descendants whose skills were not mincing information in ever finer quantities but making and doing things. In fact, productive descendants were the principal benefactors of the computer revolution. It was those machines whose well-developed supply chains fed the quantities of cards and relays and vacuum tubes and transistors necessary for computing to grow up. Those machines were responsible for the reliable manufacture of computers themselves, without which there would be no Moore’s Law.

Computing theories started to feed back into industrial application before 1940 and computing technologies followed with minicomputers and, by 1980, the low-cost microprocessor had become established as a credible tool for real-time process control.

With home computers, we think of an 8-bit era that stretched from around the late seventies until the mid eighties. With process control, it was an epoch that is only now concluding. In fact, my biggest source of information about old PLC systems is auction listings for new-in-box spares, some in storage since I was born.

Télémécanique began a hundred years ago in Nanterre, France as the original manufacturer of contactors. A contactor is a type of relay able to reliably switch high electrical currents. If you plug your car into a curbside charging station and hear a clunk, that’s an electromechanical contactor switching power.

Relays could be stuffed into racks to implement complex logic and switching tasks — the 19 inch rack standard for data centers is based on the 1920’s AT&T standard for 19” relay racks in telephone exchanges. Relays could also be distributed across a factory floor. No need for a central processing unit if there is no center to speak of. To the extent that relay systems were programmed, it was mostly with wires. The programming language was ’ladder logic’ diagrams which provided the schematic. Remember how graphical programming languages were going to take over the world and have memory safety and concurrency and make it possible for non-programmers to program? That already happened.

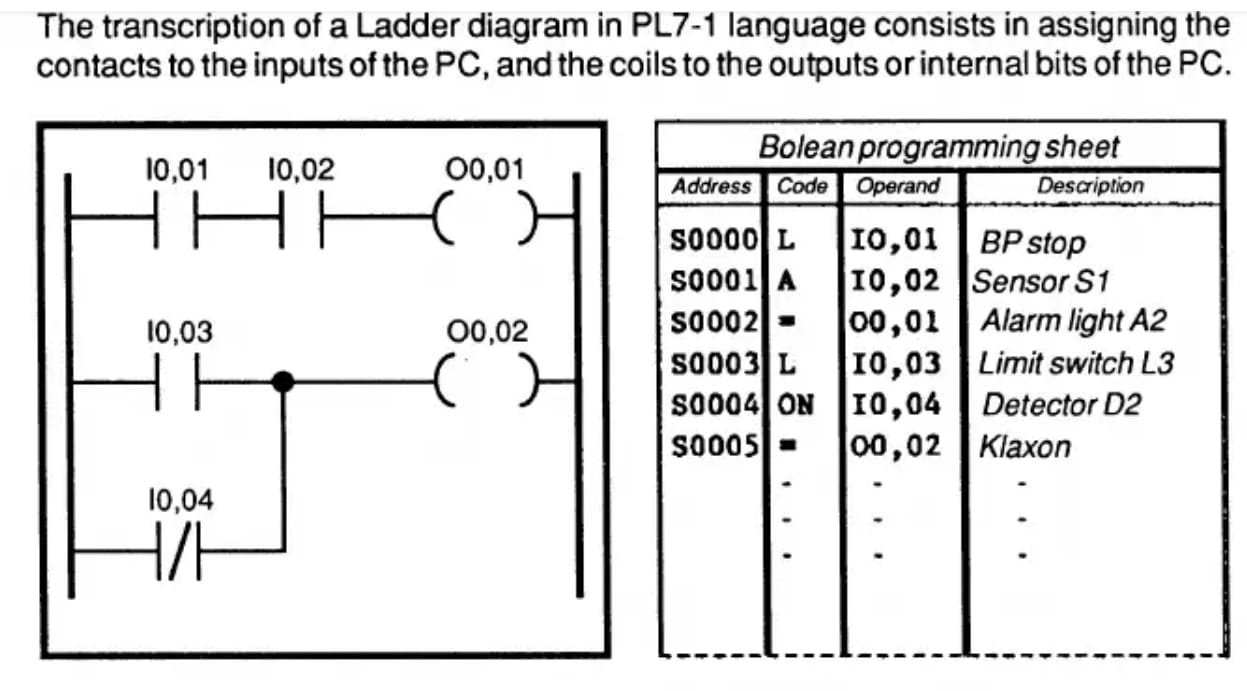

When the microprocessor arrived on the factory floor, it came not as a general-purpose adding machine but a general-purpose relay replacement. It was programmed with languages aligned with relay logic diagrams. For the TSX 17, and for many similar systems, programming was done with a detachable programmer — essentially a smart, portable terminal that connected to the device in the factory floor that could encode instructions and troubleshoot problems. For the TSX 17, the language used on the floor was PL7-1. Here’s the flavor:

24k is a somewhat unusual size. If I had to guess, rather, if I wished to guess so that I could bring this in for a landing without another of hour of research, I would guess that the smaller TSX 17-10 with 8k RAM was designed to support 1 thousand encoded steps of 8 bytes each and that the larger TSX 17-20 with 24k RAM could handle 2 thousand encoded steps with a step of 12 bytes, the difference being a larger operand size for more external I/O and deeper references to internal statements. Aside from their sexy SCADA cousins, PLC systems are infrequent targets of open-source reverse engineering so your guess is as good as mine!

This post pairs well with “Pure Imagination”, Timothée Chalamet on Wonka (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack), 2023.

Member discussion