Waterfalls and Glass #3

Track 2, Sector 1: The Hydroterm

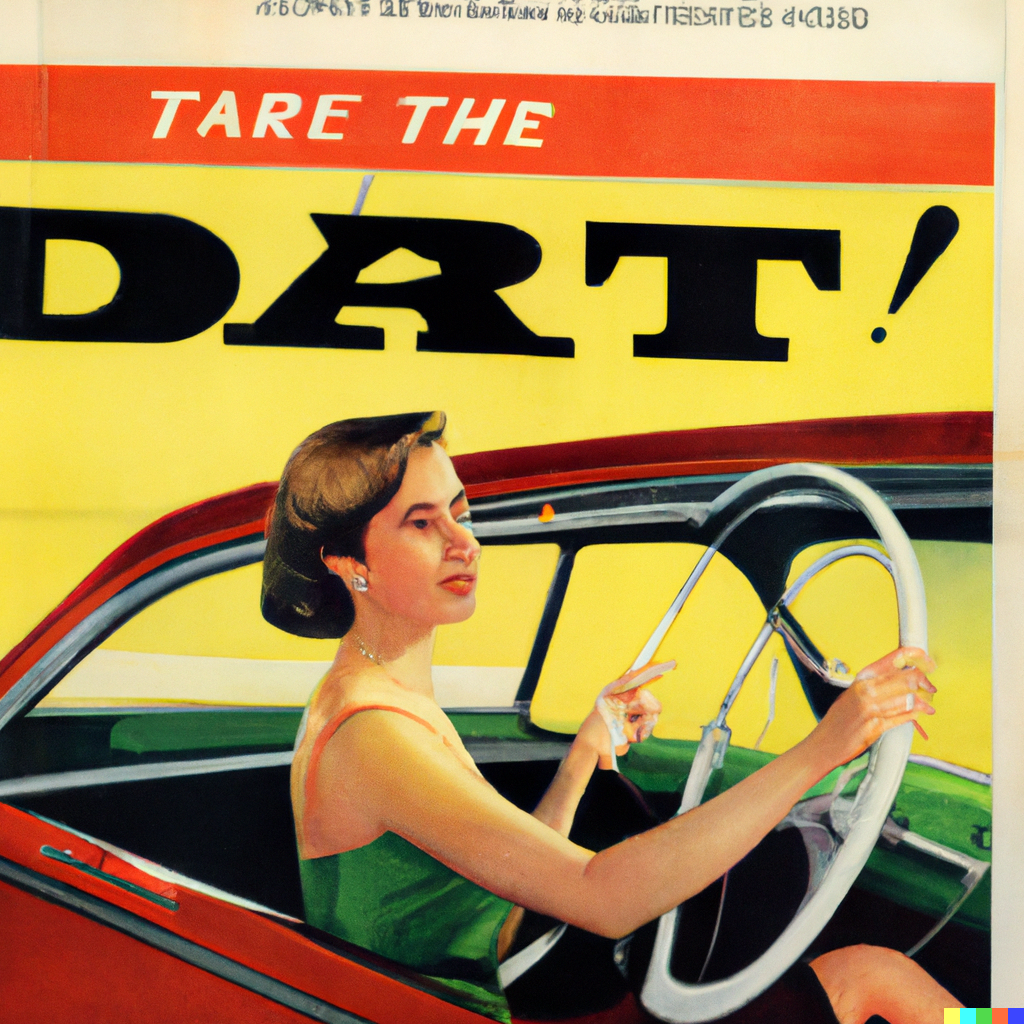

Monica slid into the driver's seat of her Dodge Dart and the vinyl upholstery compressed with the kind of gentle creaking noises that meant the easy plasticity of summer was fading. Nature supplied the little college town of Lapointe, Michigan with regular riots of color and sound to mark the context switches from Summer to Fall and so on in accordance with what must be the oldest of the time sharing systems.

Monica was occasionally struck by the beauty of the town and the surroundings but she was not attuned to it. She was attuned to car upholstery, to the electrostrictive noises of unhappy computers, to the way people spoke with their feet, and to a dozen other languages for which there was no Rosetta stone. After an evening with a crowd, after an evening with Oliver, she was just plain attenuated.

Hers was the last car in lot. She started it and set a course for home – an apartment she shared in downtown Lapointe with her roommate Susan. Monica thought that if her life were a story then she hoped her apartment would be described as a tidy apartment. It practically rolled off the tongue. Decent people had tidy apartments. Tomorrow, today already really, was Saturday and that would be a fine day to straighten up. Nobody would be by to make the story of her life before lunch in any case.

She tucked into the curb just in front and went in quietly so she wouldn't disturb Susan. Susan was asleep under her jacket on the sofa in the front room. She looked and sounded as if she would not be easily stirred so Monica let her be. She slipped off her shoes and padded quietly over to the bookcase to extract her copy of ”MILBRIDGE: The Interwar Years”. It was clearly well read and well loved. She tiptoed into the kitchen and closed the swinging door and turned on the light.

With luck, and with the light, Monica hoped she would be able to find a piece of pie. She did, but it was only strawberry rhubarb and would certainly need some coffee to make it palatable. There was an egg left for the coffee. She whisked it quietly into the pot together with the grounds and set the water to boil.

As she sat at the Formica dinette with the book and the glass pie plate, she noticed anew that the cover said ”16 color plates”. She wondered if she would ever have 16 plates. This was not a tidy apartment. All four of her plates were sitting in the sink along with what must have been Susan's. Her mother told her that it would not be suitable for her to own a service of her own as a girl by herself. She was less sure all the time that her mother was right about these things and found herself agitated if she let herself think about it.

The water boiled over before she had a chance to herself, so she got up to tend the coffee and returned to let it steep off the heat. She ran her fingers around the edges of the front cover of the book and set her head down on it for just a moment. The moment lingered for about six hours as she slept at the table. She woke when the morning sun slanted in through the window above the sink.

”I'll have a whole service of pie plates and special cups for cold coffee.” she said to the dawn.

She got up from the table to salvage the coffee. The last egg and the last of the coffee had gone into this pot so she would make what she could of it and take Susan to breakfast at the diner when she came to. Now it was the job of the pie to make the coffee palatable.

She took a bite, a sip, and a deep breath as she opened the book.

Monica read the first few sentences in a whisper. She had read through this book countless times since she had first received it as a present a decade ago.

”The MILBRIDGE syndicate remains a shining example of American industry, academy, and diplomacy working together to advance the cause of Freedom on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1915, the heads of American firms Merrimac Tabulator Incorporated and Denbridge Aldehyde joined with the Provost of Lapointe Institute of Technology of Lapointe, Michigan to create a new technology syndicate to assist the Department of State with its missions abroad.”

She knew this book well and she looked at it often when she needed inspiration. Her exploration of it had never been linear. It was rooted in the captivating and sometimes absurd pictures and drawings and radiated outward from them to the caption and then the prose. She wasn't sure that she really knew the book in order it was meant to be read, and her knowledge of some world events came exclusively from the book.

She flipped to the ghostly black-and-white photograph of the French submarine in dry dock. The exposure of the original photograph had certainly been complicated by the welders working at the time but this was likely a copy of a copy from another source published before the Germans had destroyed the original records.

The caption read ”Euler, a Brumaire-class boat, undergoes refit at Cherbourg with MILBRIDGE Systeme Hydraulique.”

Monica flipped forward a bit, past the discussion of early hydraulic programming of French mechanical torpedoes in their Drzewiecki cradles, to the picture of the black lacquer hydroterm in the wardroom of the submarine Pascal. The caption here ”Systeme Hydraulique/bis serves multiple points and multiple purposes aboard. Navalised Baudot codes control many functions.”

The surrounding text explained little about how the hydroterm actually worked but suggested that the machine was keyed silently, that it transcribed silently, and that it allowed undersea telegraphy by some undetectable hydrophonic means even when the boat was rigged for quiet running.

The black hydroterm in the photograph was a ringer for the one in the Lapointe armory. The book had a table of Baudot code but it was not clear how it had been navalized or what that would possibly mean beyond a casual swipe at the Army. The photo on the opposing page was a macro view of the beautiful knurled glass connector that could still be found on some of the devices on campus, captioned ”20 meters of additional glass filament are drawn past the sheath braid to form the Lalique-style monobloc terminus.”

A casual reader might have seen a jumble of war materiel and art glass and typewriters hybridized with organ consoles. A cynical reader would see a meandering self-published photo essay that sought to rationalize post facto a technology base that had been a rather overplayed hand for a long time. Monica saw the same marvelous machines she had seen the first time she opened it, the same hydroterms she had first seen in person when she came to Lapointe after college to work as a wire-wrap technician. In the photo of the glass connector, she could see the sturdy gray-green steel term in her own office and the way her connector caught the window’s light at certain moments in the morning and concentrated it into the single drip of Denbridge fluid that was perpetually half-formed on the bottom.

She looked again at the hydroterm in the photo, but this time pressing her nose almost against the page. The text on that hydroterm scroll was too small to be legible but it was certainly darker than text printed on terminals recently. When Douglas Macarthur had addressed the Congress a decade earlier, he said that old soldiers never die – they just fade away. The hydroterm was of much the same mind. She thought about the player piano back home. It too was running out of fresh scroll. In the case of the hydroterm, there were plenty of rolls of the special paper left. Lapointe now had what might be the rest of the world's supply and it could last until doomsday. Less long if the stuff that felt perpetually damp could be used for any other purpose whatsoever. The problem was that it was slowly degrading.

Though Merrimac had always made the hydroterm machines, Denbridge invented the paper and the special process for catalytic printing with a platinum typeblock. Denbridge stopped making the paper when the market for dollar-a-page silent printing, small even in wartime, dried up. Lapointe had been able to buy the remaining stock for little more than the cost of shipping and a promise that they would not incinerate the waste or allow children or pregnant women to handle it. Those terms had been easy enough -- Lapointe was a university campus, after all, not a petting zoo!

Susan came into the kitchen. This was not enough to break Monica's reverie but the swinging door sounding THONK THONK, Thonk thonk, (thonk thonk) as it damped itself in her wake did the trick.

With the spell now broken, Susan pounced. ”Monnie, how long have you been hiding in here looking at that?”

”Let's have pie for breakfast, my treat.“

Member discussion